Titanic: Getting Started With R - Part 2: The Gender-Class Model

In the previous lesson, we covered the basics of navigating data in R, but only looked at the target variable as a predictor. Now it’s time to try and use the other variables in the dataset to predict the target more accurately.

The disaster was famous for saving “women and children first”, so let’s take a look at the Sex and Age variables to see if any patterns are evident. We’ll start with the gender of the passengers. After reloading the data into R, take a look at the summary of this variable:

> summary(train$Sex)

female male

314 577

So we see that the majority of passengers were male. Now let’s expand the proportion table command we used last time to do a two-way comparison on the number of males and females that survived:

> prop.table(table(train$Sex, train$Survived))

0 1

female 0.09090909 0.26150393

male 0.52525253 0.12233446

Well that’s not very clean, the proportion table command by default takes each entry in the table and divides by the total number of passengers. What we want to see is the row-wise proportion, ie, the proportion of each sex that survived, as separate groups. So we need to tell the command to give us proportions in the 1st dimension which stands for the rows (using “2” instead would give you column proportions):

> prop.table(table(train$Sex, train$Survived),1)

0 1

female 0.2579618 0.7420382

male 0.8110919 0.1889081

Okay, that’s better. We now can see that the majority of females aboard survived, and a very low percentage of males did. In our last prediction we said they all met Davy Jones, so changing our prediction for this new insight should give us a big gain on the leaderboard! Let’s update our old prediction and introduce some more R syntax:

> test$Survived <- 0

> test$Survived[test$Sex == 'female'] <- 1

Here we have begun with adding the “everyone dies” prediction column as before, except that we’ll ditch the rep command and just assign the zero to the whole column, it has the same effect. We then altered that same column with 1’s for the subset of passengers where the variable “Sex” is equal to “female”.

We just used two new pieces of R syntax, the equality operator, ==, and the square bracket operator. The square brackets create a subset of the total dataframe, and apply our assignment of “1” to only those rows that meet the criteria specified. The double equals sign no longer works as an assignment here, now it is a boolean test to see if they are already equal.

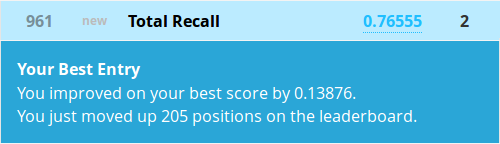

Now let’s write a new submission and send it to Kaggle to see how it’s improved our position!

Nice! We’re getting there, but let’s start digging into the age variable now:

> summary(train$Age)

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max. NA's

0.42 20.12 28.00 29.70 38.00 80.00 177

It is possible for values to be missing in data analytics, and this can cause a variety of problems out in the real world that can be quite difficult to deal with at times. For now we could assume that the 177 missing values are the average age of the rest of the passengers, ie. late twenties.

Our last few tables were on categorical variables, ie. they only had a few values. Now we have a continuous variable which makes drawing proportion tables almost useless, as there may only be one or two passengers for each age! So, let’s create a new variable, “Child”, to indicate whether the passenger is below the age of 18:

> train$Child <- 0

> train$Child[train$Age < 18] <- 1

As with our prediction column, we have now created a new column in the training set dataframe indicating whether the passenger was a child or not. Beginning with the assumption that they were an adult, and then overwriting the value for passengers below the age of 18. To do this we used the less than operator, which is another boolean test, similar to the equality check used in our last predictions. If you click on the train object in the explorer, you will see that any passengers with an age of NA have been assigned a zero, this is because the NA will fail any boolean test. This is what we wanted though, since we had decided to use the average age, which was an adult.

Now we want to create a table with both gender and age to see the survival proportions for different subsets. Unfortunately our proportion table isn’t equipped for this, so we’re going to have to use a new R command, aggregate. First let’s try to find the number of survivors for the different subsets:

> aggregate(Survived ~ Child + Sex, data=train, FUN=sum)

Child Sex Survived

1 0 female 195

2 1 female 38

3 0 male 86

4 1 male 23

The aggregate command takes a formula with the target variable on the left hand side of the tilde symbol and the variables to subset over on the right. We then tell it which dataframe to look at with the data argument, and finally what function to apply to these subsets. The command above subsets the whole dataframe over the different possible combinations of the age and gender variables and applies the sum function to the Survived vector for each of these subsets. As our target variable is coded as a 1 for survived, and 0 for not, the result of summing is the number of survivors. But we don’t know the total number of people in each subset; let’s find out:

> aggregate(Survived ~ Child + Sex, data=train, FUN=length)

Child Sex Survived

1 0 female 259

2 1 female 55

3 0 male 519

4 1 male 58

This simply looked at the length of the Survived vector for each subset and output the result, the fact that any of them were 0’s or 1’s was irrelevant for the length function. Now we have the totals for each group of passengers, but really, we would like to know the proportions again. To do this is a little more complicated. We need to create a function that takes the subset vector as input and applies both the sum and length commands to it, and then does the division to give us a proportion. Here is the syntax:

> aggregate(Survived ~ Child + Sex, data=train, FUN=function(x) {sum(x)/length(x)})

Child Sex Survived

1 0 female 0.7528958

2 1 female 0.6909091

3 0 male 0.1657033

4 1 male 0.3965517

Well, it still appears that if a passenger is female most survive, and if they were male most don’t, regardless of whether they were a child or not. So we haven’t got anything to change our predictions on here. Let’s take a look at a couple of other potentially interesting variables to see if we can find anything more: the class that they were riding in, and what they paid for their ticket.

While the class variable is limited to a manageable 3 values, the fare is again a continuous variable that needs to be reduced to something that can be easily tabulated. Let’s bin the fares into less than $10, between $10 and $20, $20 to $30 and more than $30 and store it to a new variable:

> train$Fare2 <- '30+'

> train$Fare2[train$Fare < 30 & train$Fare >= 20] <- '20-30'

> train$Fare2[train$Fare < 20 & train$Fare >= 10] <- '10-20'

> train$Fare2[train$Fare < 10] <- '<10'

Now let’s run a longer aggregate function to see if there’s anything interesting to work with here:

> aggregate(Survived ~ Fare2 + Pclass + Sex, data=train, FUN=function(x) {sum(x)/length(x)})

Fare2 Pclass Sex Survived

1 20-30 1 female 0.8333333

2 30+ 1 female 0.9772727

3 10-20 2 female 0.9142857

4 20-30 2 female 0.9000000

5 30+ 2 female 1.0000000

6 <10 3 female 0.5937500

7 10-20 3 female 0.5813953

8 20-30 3 female 0.3333333 **

9 30+ 3 female 0.1250000 **

10 <10 1 male 0.0000000

11 20-30 1 male 0.4000000

12 30+ 1 male 0.3837209

13 <10 2 male 0.0000000

14 10-20 2 male 0.1587302

15 20-30 2 male 0.1600000

16 30+ 2 male 0.2142857

17 <10 3 male 0.1115385

18 10-20 3 male 0.2368421

19 20-30 3 male 0.1250000

20 30+ 3 male 0.2400000

While the majority of males, regardless of class or fare still don’t do so well, we notice that most of the class 3 women who paid more than $20 for their ticket actually also miss out on a lifeboat, I’ve indicated these with asterisks, but R won’t know what you’re looking for, so they won’t show up in the console.

It’s a little hard to imagine why someone in third class with an expensive ticket would be worse off in the accident, but perhaps those more expensive cabins were located close to the iceberg impact site, or further from exit stairs? Whatever the cause, let’s make a new prediction based on the new insights.

> test$Survived <- 0

> test$Survived[test$Sex == 'female'] <- 1

> test$Survived[test$Sex == 'female' & test$Pclass == 3 & test$Fare >= 20] <- 0

Most of the above code should be familiar to you by now. The only exception would be that there are multiple boolean checks all stringed together for the last adjustment. For more complicated boolean logic, you can combine the logical AND operator & with the logical OR operator |.

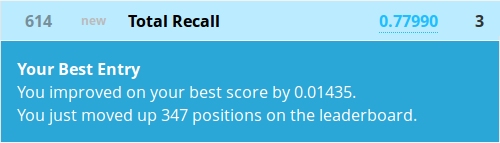

Okay, let’s create the output file and see if we did any better!

Alright, now we’re getting somewhere! We only improved our accuracy score by 1.5%, but jumped hundreds of spots on the leaderboard! But that was a lot of work, and creating more subsets that dive much deeper would take a lot of time.

Next lesson, we will automate this process by using decision trees. Go there now!

All code from this tutorial is available on my Github repository

Leave a Comment